Christi Belcourt

Take Only What You Need

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Take Only What You Need

By Suzanne Luke

University Art Curator, Robert Langen Art Gallery

The rich history of Indigenous art practices continues to evolve and re-shape itself as contemporary Indigenous artists push boundaries, to create innovative ways to intertwine the historical past with new hopes for the future. The impact of the Canadian federal residential school system (1831–1996) not only forcibly separated children from their families, but lead to the loss of Indigenous traditions, cultural practices, and languages. This erasure of identity also resulted in the suppression of creative Indigenous artistic expressions.

In 2015, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, along with its 94 Calls to Action, sought to address the devastating legacy of residential schools and initiate a path toward healing and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. This journey remains an ongoing process. By fostering culturally safe environments within the arts and cultural sectors, we take meaningful steps toward decolonization while honoring and embracing Indigenous identities and artistic practices.

The Robert Langen Art Gallery (RLAG) is committed to integrating Indigenous knowledge and artistic practices in its exhibition programs and activities. By amplifying Indigenous voices, the gallery provides a platform where distinct creative knowledge can be the catalyst to inspire dialogue, understanding and change. It is important to recognize that artistic expression whether visual, literary, or performing can play a vital role in the process of reconciliation and healing.

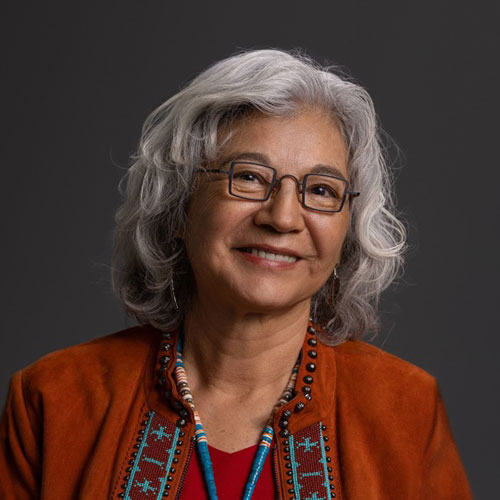

I had the immense pleasure of collaborating with Metis artist, environmentalist, and social justice advocate Christi Belcourt in 2022 to present Take Only What You Need. In this exhibition, Belcourt invited viewers to self reflect on nature’s symbolic properties and the earthly connections between human existence and the natural world. Her vibrant use of colour and meticulous diligence created visual landscapes of wonder, challenging audiences to acknowledge their dependence on and responsibility for the survival of Mother Earth.

Christi Belcourt (apihtâwikosisâniskwêw / mânitow sâkahikanihk) is a visual artist with profound respect for the traditions and knowledge of her people. Like generations of Indigenous artists before her, she celebrates the beauty of the natural world while exploring its symbolic meanings. In Take Only What You Need her works serve as a call to action, urging people to cherish and protect the environment and celebrate the beauty, fragility, and mysteries of the world around us. As Belcourt states:

“We, humans, are at the bottom, not the top, as we rely on every living thing to survive, and nothing relies on us except perhaps our domesticated pets. I call on people to connect with their deep love for those places on earth where they feel most connected. I call on people to connect and take action to protect the waters nearest to them. I call on people to stand up for the coming generations.”

In 1993, Belcourt embarked on an artistic exploration to paint flowers inspired by the beadwork patterns of Métis and First Nations women. This experiment with circular shapes soon blossomed into an art practice that pays homage to the traditional beadwork of her ancestors while honouring the spiritual interconnectedness of the universe, all living beings and traditional medicines. Her distinctive art practice honours the study of plants, lands, and waters. Belcourt’s large-scale paintings are composed of over 200,000 meticulously placed dots that give a voice to Indigenous history, mysticism, and cultural identity.

Belcourt’s works frequently address issues of environmental justice and Indigenous rights. Honouring my Spirit Helpers (2010), and So Much Depends Upon Who Holds the Shovel (2008) call into question the imbalance between corporate power and community agency. Beneath the beauty of the vibrant flora and fauna, these works reveal the interconnectedness of water, earth, life, and all species. Reminding us that we are collectively rooted together and urging us to reassess unsustainable practices that threaten Mother Earth.

An environmentalist and social justice advocate, Belcourt deeply respects the traditions and knowledge of her Indigenous ancestors. What the Sturgeon Told Me (2007), and Fish are Fasting for Knowledge (2018) exemplifies her commitment to sharing and educating viewers on ancestral wisdom. In these paintings the sturgeon and the fish serve as carriers of knowledge, offering critical lessons about consequences of environmental disruptions and the necessity of respecting the natural world. The sacred knowledge that animals hold and the need for humans to respect and protect these relationships are a central theme in Belcourt’s work.

To conclude Take Only What You Need, Belcourt created two new paintings: The Frogs Sign Loudly in Spring (2021) and Roots (2021). Once again, these works encapsulate the spirituality of nature; reminding us that co-existence extends beyond what we see. The intricate root systems depicted in these paintings interconnect all life forms, they support life and hold space between our present and ancestral past. As Belcourt reflects:

“Roots remind me that there is a bigger picture, a grand mystery to which we are all connected. They soak up the power of Mother Earth, and when we ingest them, we take that power into ourselves to heal. Roots hold together the soil; they ground us and sustain life on the planet.”

Belcourt’s artistic practice is deeply rooted in her Métis heritage, reflecting a profound respect for ancestral traditions and knowledge. With great intentionality, her work celebrates the beauty of the natural world while addressing pressing issues of cultural identity, land stewardship, and social justice. Beyond her artistic achievements, she has been a driving force behind community initiatives such as Walking With Our Sisters (2012–2021), a national touring commemoration honoring Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people. She was also instrumental in the Willisville Mountain Project (2010–2013), which successfully halted a mining company’s plans to quarry Willisville Mountain. Through the Onaman Collective and Nimkii Aazhibikong, a year-round land-based arts and language space in Northeastern Ontario, she continues her advocacy for Indigenous culture and environmental sustainability.

It was a tremendous honor to present Take Only What You Need and to welcome Christi Belcourt to the Robert Langen Art Gallery. I extend my deepest gratitude to her for her generosity, vision, and dedication to this project.

By Christi Belcourt

When you look at Indigenous art traditions around the world, there is often a direct connection to the land implied in some way within the art. Its no different for Metis People who were historically known as “The Flower Beadwork People.” The understanding of how we’re supposed to live on the land is encoded into our beliefs which are sometimes found in the designs and symbols present in our artwork.

When I’m creating my art, I’m not simply transferring beadwork patterns onto the canvas; there has to be meaning behind it. So I will include certain plants or symbols into the painting that have a specific reason or coding behind them. It’s always primarily a message about the respect for lands and waters: the respect we need to have for the earth and everything that is around us. As human beings, we are mistaken if we think we are superior to other species.

My heart overflows with love for the beauty of this world.

I see war, but I paint flowers.

I paint what I want for this world. I try to reflect to the best of my ability the power and sacredness of Mother Earth which is the sacredness of all life as we know it.

May we live long enough to see humankind turn away from violence and greed and towards creating a world based on caring and giving. May we live long to see the world embrace global disarmament.

Prayers for the sick to be healed.

For the bombs to stop.

Freedom and dignity, care and enough for all.

Louise Bernice Halfe, whose Cree name is Sky Dancer, is Canada's ninth Parliamentarian Poet Laureate and served as the first Indigenous Poet Laureate of Saskatchewan.

She was born in Two Hills, Alberta, raised on the Saddle Lake First Nation and attended Blue Quills Residential School. She earned her Bachelor of Social Work from the University of Regina and certificates in Addiction Counselling from the Nechi Institute.

She earned her Doctor of Letters from Wilfrid Laurier University, the University of Saskatchewan and Mount Royal University.

Halfe's poetry collections include Bear Bones & Feathers, Blue Marrow, The Crooked Good and Burning in this Midnight Dream. Her latest poetry collection is awâsis – kinky and disheveled.

Oliver Manidoka is a Laurier alumnus and former employee of Laurier’s Indigenous Student Services. With a deep passion for storytelling and performance, he has recently embarked on a journey into voice work, specializing in narrations and short stories.

By Kim Anderson

Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Relationality and Storied Practice

Professor, Family Relations and Applied Nutrition at University of Guelph

May 2024

In recent years it’s become common to offer land acknowledgements at the opening of events or activities, particularly in university settings. As a professor at the University of Guelph, I often ponder ways to introduce land acknowledgments in a more meaningful manner than simply reciting the words. I encourage students to reflect more deeply about how they can take up responsibilities within their personal and professional lives. We talk about responsibilities to the particular Indigenous knowledges and peoples of the lands we inhabit. We explore how land acknowledgements can be part of everyday living and discuss how they can be expressed in many ways. To me, Take Only What You Need is one such expression.

Christi Belcourt’s Take Only What You Need exhibition took place on the campus of Wilfrid Laurier University (WLU) in the fall of 2022, As I prepared to write this essay, I revisited the land acknowledgement on the WLU website. It states that WLU’s Waterloo campus is part of the Haldimand Proclamation, land provided to Six Nations of the Grand River, and that WLU is also within the Dish with One Spoon territory. The metaphor of a dish that warring nations can learn to share peacefully dates back to the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace and was later employed in the 1701 Dish with One Spoon Treaty between the Anishinaabek and the Haudenosaunee. The agreement served as a reminder to these diverse Indigenous nations that they could mutually enjoy and at the same time, co-operatively sustain the resources of the Great Lakes region. It spoke to upholding responsibilities to the lands and waters that persist to this day.

The WLU land acknowledgement led me to reflect on the teachings of Richard (Rick) Hill, a Tuscarora historian. Hill has often said there are three basic principles of The Dish with One Spoon: (1) take only what you need; (2) always leave something in the dish for everybody else; and (3) keep the dish clean.1 In times of strife, the Dish has thus been used to remind us to resolve our human conflicts and remember our treaties with the natural world. In speaking about the Dish, Hill has also referenced wise words from Oren Lyons; that “There can never be world peace as long as you make war against Mother Earth…. The first peace is with your mother, Mother Earth.”2

With this land acknowledgement in mind, I turned to Christi Belcourt’s invitation to “take only what you need.” I began to consider what it is we need, and what it is we might take as we find ourselves grappling with strife in the year 2024. I thought about the poem that Louise Halfe wrote in response to Christi’s exhibition. I thought about the consequences of warring with Mother Earth, and with each other. I am grateful for the works of artists like Christi Belcourt and Louise Halfe, and for the teachings of historians like Rick Hill, as they can help us consider the following key questions of our times: How might we renew or develop new treaties between ourselves and the natural world as we face seemingly insurmountable challenges of climate crisis and human conflict? How can we make peace? These are questions that underpin my everyday worries, and the concerns that I see in the young people I teach.

So what do we need?

I believe we need the beauty, love, wisdom, and hope provided by what is still in the Dish, and Christi Belcourt provides us these medicines through her art. There is an exquisite beauty in all of Christi’s work, showing her love for the land and encouraging viewers to remember the same. What I want to share is that the paintings in Take Only What You Need offer other layers of the very knowledge we need right now. This is because her work is an honouring of the deep wisdom of the Dish; it draws our attention to the roots and the celestial connections. And then there’s hope.

To me there is hope in the ongoing presence that Christi captures in the intricate detail and complexity of the lands, waters, and more-than-human relations living in the Dish that is the Great Lakes region. She helps us to see the things that we might have forgotten or overlooked; she reminds us that the plants are still growing, fish are still fasting, frogs are still singing. With the help of relations like the sturgeon, we can still dream. We can work with all our relations in practices of revival, as the Menominee have shown in their ceremonies involving the sturgeon. We can recognize the work that is done between non-humans, like the sturgeon and the frogs.

Hope also comes when we see what can be accomplished if we take up our responsibilities. It comes when we see how art can be a part of change, and art for change is a significant part of Christi’s practice. I have seen this through my involvement with Walking with Our Sisters, a commemorative art installation that grew out of Christi’s need to do something to address the staggering number of missing and murdered Indigenous women across North America. This involved putting out a call for people to send in beaded vamps, the top portion of moccasins, which she intended to use to represent the unfinished lives of the women. Christi initially hoped to get a few hundred vamps; in the end, there were 1,763. Walking with Our Sisters travelled to over 25 locations in distinct installations created in collaboration with the local host Indigenous communities.

Through Take Only What You Need, I learned about one of Christi’s earlier art activist projects: her painting Inco Killing the Sacred was part of touring show that eventually stopped the destruction of Willsville Mountain. Though we can’t always control “who is holding the shovel,” there is hope in these collaborative artivist projects, and there can be change.

So what do we take? Beauty, love, wisdom, hope. A reminder of how to acknowledge the lands we find ourselves in. Perhaps this is what Christi means when she says her work is a call to action. So here are a few calls I thought of for myself as I pondered Take Only What You Need:

That’s what I need, for now.

Ekosi

As I was finishing this essay, I bumped into a Métis colleague I hadn’t seen in some time. While we were catching up, she coincidentally mentioned that she had travelled to see Take Only What You Need when it opened at the Robert Langen Art Gallery, bringing her seven-year-old son with her. Without knowing that I was working on this essay, she began by describing Inco Killing the Sacred to me: “There are people and animals in it, looking afraid, and a tower.” She then went on to describe her son’s reaction to Inco Killing the Sacred, which I offer here with their permission. The young boy’s first comment was about how the animals and people looked scared. But then he pointed to the bear. He noted that she was still doing her responsibilities of taking care of people.

This story struck me as poignant in so many ways. The child knew about the responsibilities of bears as healers and protectors. It gave me hope that Indigenous children today are being raised with the kind of knowledge that many of us — due to having it being beaten out of our parents — did not grow up with. I could see that knowledge moves in a circular motion; we are constantly learning from our children, and they from us; the ancestors and all the other relations, seen and unseen, are connected as they are in Christi’s paintings. The younger generations, in these difficult times, can recognize that there are protectors out there and that they can work with them. There are new generations in the Dish that know their relations. We will work with them into the future.

1 2 There are many places where one can find Rick Hill discussing the Dish with One Spoon. The one that cites Oren Lyons is from Six Nations Polytechnic: Ecological Knowledge and the Dish with One Spoon: Conversation in Cultural Fluency #2

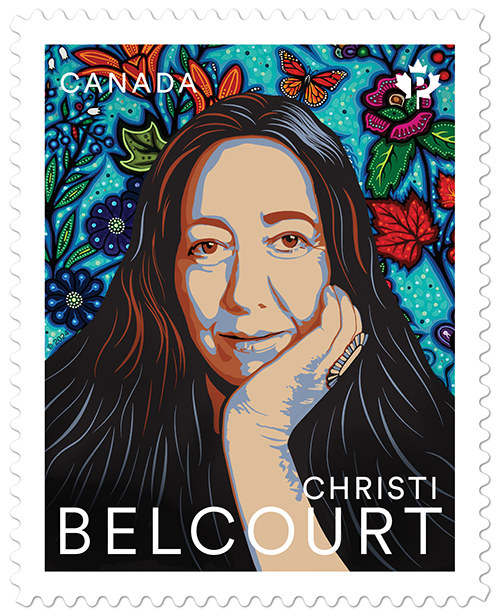

Christi Belcourt is one of three distinguished women featured in Canada Post’s 2024 Indigenous Leaders series, alongside Elisapie — an award-winning singer-songwriter, actor, director, producer, and activist — and Josephine Mandamin, an Anishinaabe Elder and world-renowned water-rights advocate.

The Indigenous Leaders series celebrates First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leaders who are dedicated to preserving their culture and advocating for the well-being of Indigenous Peoples. Belcourt’s stamp in the 2024 collection is inspired by her painting Reverence for Life, reflecting her deep connection to nature and Indigenous traditions.

Belcourt’s artistic achievements have been widely recognized, earning her numerous awards and grants from organizations such as the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts. Among her many honors are the Order of Canada (2024), the Jim Brady Memorial Medal of Excellence (2023), the Premier’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts (Ontario, 2016), Governor General’s Innovation Award (2016), Women of Northern Ontario’s Aboriginal Leadership Award (2014), the 2014 Ontario Arts Council Aboriginal Arts Award and an Aboriginal Leadership Award, the Laureate of the Aboriginal Arts, Ontario Arts Council (2014).

Additionally, Belcourt has received two honorary doctorate degrees from Algoma University, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario.